Jets¶

To do

Only basic 4-vector access information has been added for Run 2 data

What are jets?¶

Jets are spatially-grouped collections of long-lived particles that are produced when a quark or gluon hadronizes. The kinematic properties of jets resemble that of the initial partons that produced them. In the CMS language, jets are made up of many particles, with the following predictable energy composition:

- ~65% charged hadrons

- ~25% photons (from neutral pions)

- ~10% neutral hadrons

Jets are very messy! Hadronization and the subsequent decays of unstable hadrons can produce 100s of particles near each other in the CMS detector. Hence these particles are rarely analyzed individually. How can we determine which particle candidates should be included in each jet?

Clustering¶

Jets can be clustered using a variety of different inputs from the CMS detector. "CaloJets" use only calorimeter energy deposits. "GenJets" use generated particles from a simulation. But by far the most common are "PFJets", from particle flow candidates.

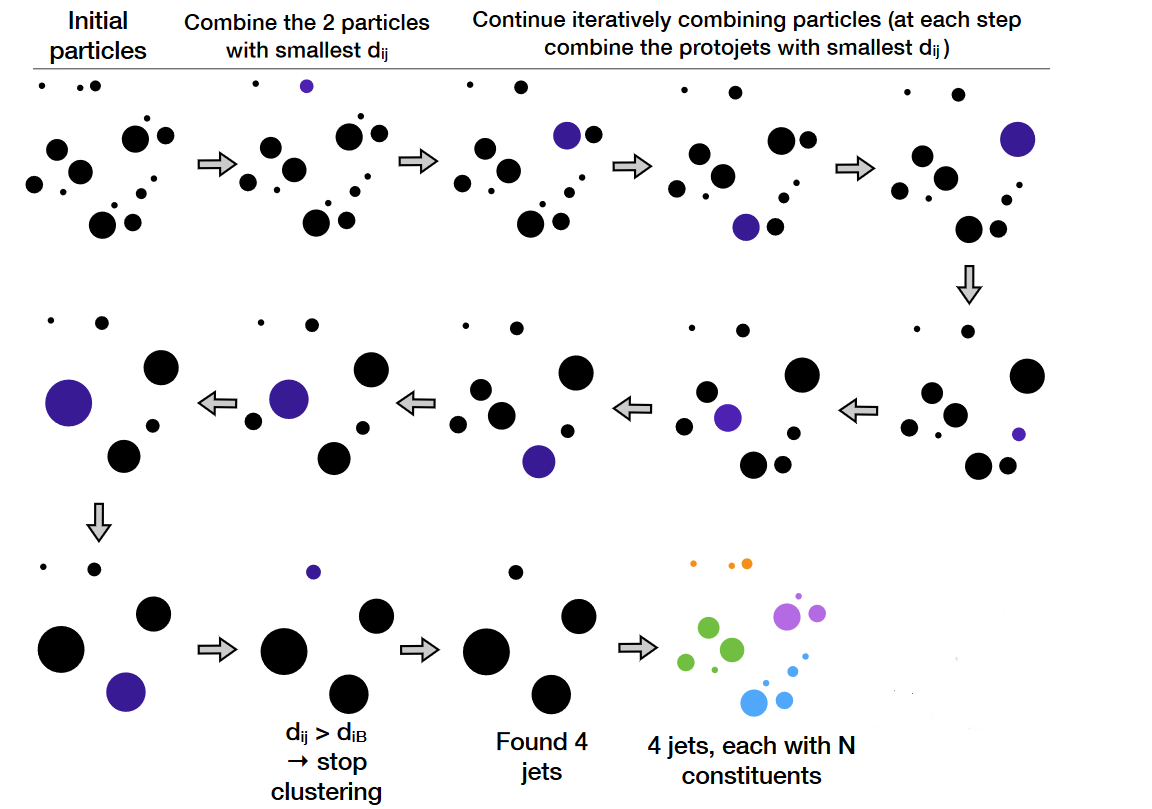

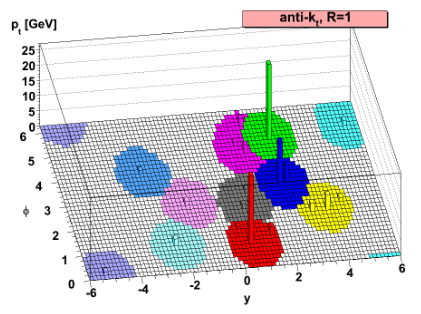

The result of the CMS Particle Flow algorithm is a list of particle candidates that account for all inner-tracker and muon tracks and all above-threshold energy deposits in the calorimeters. These particles are formed into jets using a "clustering algorithm". The most common algorithm used by CMS is the "anti-kt" algorithm, which is abbreviated "AK". It iterates over particle pairs and finds the two (i and j) that are the closest in some distance measure and determines whether to combine them:

The momentum power (-2) used by the anti-kt algorithm means that higher-momentum particles are clustered first. This leads to jets with a round shape that tend to be centered on the hardest particle. In CMS software this clustering is implemented using the fastjet package.

Pileup¶

Inevitably, the list of particle flow candidates contains particles that did not originate from the primary interaction point. CMS experiences multiple simultaneous collisions, called "pileup", during each "bunch crossing" of the LHC, so particles from multiple collisions coexist in the detector. There are various methods to remove their contributions from jets:

- Charged hadron subtraction CHS: all charged hadron candidates are associated with a track. If the track is not associated with the primary vertex, that charged hadron can be removed from the list. CHS is limited to the region of the detector covered by the inner tracker. The pileup contribution to neutral hadrons has to be removed mathematically which will be discussed later.

- PileUp Per Particle Identification (PUPPI, available in Run 2): CHS is applied, and then all remaining particles are weighted based on their likelihood of arising from pileup. This method is more stable and performant in high pileup scenarios such as the upcoming HL-LHC era.

Accessing Jets in CMS Software¶

Two examples of EDAnalyzers accessing jet information are available in the Physics Object Extractor Tool (POET):

- JetAnalyzer accessing jets from the

PFJetCollection - PatJetAnalyzer accessing jets from

std::vector<pat::Jet>collection using "Physics Analysis Toolkit" (PAT) format in which jets are easier to work with.

The following header files needed for accessing jet information are included:

//classes to extract PFJet information

#include "DataFormats/JetReco/interface/PFJet.h"

#include "DataFormats/JetReco/interface/PFJetCollection.h"

#include "DataFormats/BTauReco/interface/JetTag.h"

#include "CondFormats/JetMETObjects/interface/JetCorrectionUncertainty.h"

#include "CondFormats/JetMETObjects/interface/FactorizedJetCorrector.h"

#include "CondFormats/JetMETObjects/interface/JetCorrectorParameters.h"

#include "CondFormats/JetMETObjects/interface/SimpleJetCorrector.h"

#include "CondFormats/JetMETObjects/interface/SimpleJetCorrectionUncertainty.h"

#include "DataFormats/VertexReco/interface/Vertex.h"

#include "DataFormats/VertexReco/interface/VertexFwd.h"

#include "DataFormats/JetReco/interface/Jet.h"

#include "SimDataFormats/JetMatching/interface/JetFlavourInfo.h"

#include "SimDataFormats/JetMatching/interface/JetFlavourInfoMatching.h"

Jets software classes have the same basic 4-vector methods as the objects discussed in the Common Tools page. In JetAnalyzer.cc, the jet four-vector elements are accessed (with jetInput passed as "ak5PFJets" in the configuration file) :

Handle<reco::PFJetCollection> myjets;

iEvent.getByLabel(jetInput, myjets);

[...]

for (reco::PFJetCollection::const_iterator itjet=myjets->begin(); itjet!=myjets->end(); ++itjet){

[...]

jet_e.push_back(itjet->energy());

jet_pt.push_back(itjet->pt());

jet_px.push_back(itjet->px());

jet_py.push_back(itjet->py());

jet_pz.push_back(itjet->pz());

jet_eta.push_back(itjet->eta());

jet_phi.push_back(itjet->phi());

[...]

}

An example of an EDAnalyzer accessing jet information is available in the JetAnalyzer of the Physics Object Extractor Tool (POET). The following header file needed for accessing MET information is included:

//class to extract jet information

#include "DataFormats/PatCandidates/interface/Jet.h"

Jets software classes have the same basic 4-vector methods as the objects discussed in the Common Tools page. In JetAnalyzer.cc, the jet four-vector elements are accessed from the pat::Jet collection as shown below

Handle<pat::JetCollection> jets;

iEvent.getByToken(jetToken_, jets);

[...]

for (const pat::Jet &jet : *jets)

{

jet_e.push_back(jet.energy());

jet_pt.push_back(jet.pt());

jet_px.push_back(jet.px());

jet_py.push_back(jet.py());

jet_pz.push_back(jet.pz());

jet_eta.push_back(jet.eta());

jet_phi.push_back(jet.phi());

[...]

}

jetToken_ is defined as a member of the MetAnalyzer class and its value read from the configuration file.

Jet ID¶

Particle-flow jets are not immune to noise in the detector, and jets used in analyses should be filtered to remove noise jets. CMS has defined a Jet ID with criteria for good jets:

The PFlow jets are required to have charged hadron fraction CHF > 0.0 if within tracking fiducial region of |eta| < 2.4, neutral hadron fraction NHF < 1.0, charged electromagnetic (electron) fraction CEF < 1.0, and neutral electromagnetic (photon) fraction NEF < 1.0. These requirements remove fake jets arising from spurious energy depositions in a single sub-detector.

These criteria demonstrate how particle-flow jets combine information across subdetectors. Jets will typically have energy from electrons and photons, but those fractions of the total energy should be less than one. Similarly, jets should have some energy from charged hadrons if they overlap the inner tracker, and all the energy should not come from neutral hadrons. A mixture of energy sources is expected for genuine jets. All of these energy fractions (and more) can be accessed from the jet objects.

You can use the PFJet class definition of the CMSSW DataFormats package to see what methods are available for PFJets. It is rendered for maybe easier readability in the CMSSW software documentation. We can implement a jet ID to reject jets that do not pass so that these jets are not stored in any of the tree branches. This code show an implementation of Jet ID cuts while also applying a minimum momentum threshold.

for (reco::PFJetCollection::const_iterator itjet=jets->begin(); itjet!=jets->end(); ++itjet){

if (itjet->pt > jet_min_pt && itjet->chargedHadronEnergyFraction() > 0 && itjet->neutralHadronEnergyFraction() < 1.0 &&

itjet->electronEnergyFraction() < 1.0 && itjet->photonEnergyFraction() < 1.0){

// jet calculations

Note

- The code snippet above is not part of the example analyzer.

Work in progress

Jet corrections¶

To do

Description of jet corrections needs to be added, see the workshop tutorial

Work in progress

B Tagging Algorithms¶

Jet reconstruction and identification is an important part of the analyses at the LHC. A jet may contain the hadronization products of any quark or gluon, or possibly the decay products of more massive particles such as W or Higgs bosons. Several b tagging” algorithms exist to identify jets from the hadronization of b quarks, which have unique properties that distinguish them from light quark or gluon jets.

Tagging algorithms first connect the jets with good quality tracks that are either associated with one of the jet’s particle flow candidates or within a nearby cone. Both tracks and “secondary vertices” (track vertices from the decays of b hadrons) can be used in track-based, vertex-based, or “combined” tagging algorithms. The specific details depend upon the algorithm use. However, they all exploit properties of b hadrons such as:

- long lifetime

- large mass

- high track multiplicity

- large semiloptonic branching fraction

- hard fragmentation function.

Tagging algorithms are Algorithms that are used for b-tagging:

- Track Counting: identifies a b jet if it contains at least N tracks with significantly non-zero impact parameters.

- Jet Probability: combines information from all selected tracks in the jet and uses probability density functions to assign a probability to each track.

- Soft Muon and Soft Electron: identifies b jets by searching for a lepton from a semi-leptonic b decay.

- Simple Secondary Vertex: reconstructs the b decay vertex and calculates a discriminator using related kinematic variables.

- Combined Secondary Vertex: exploits all known kinematic variables of the jets, information about track impact parameter significance and the secondary vertices to distinguish b jets. This tagger became the default CMS algorithm.

These algorithms produce a single, real number (often the output of an MVA) called a b tagging “discriminator” for each jet. The more positive the discriminator value, the more likely it is that this jet contained b hadrons.

Accessing Tagging Information¶

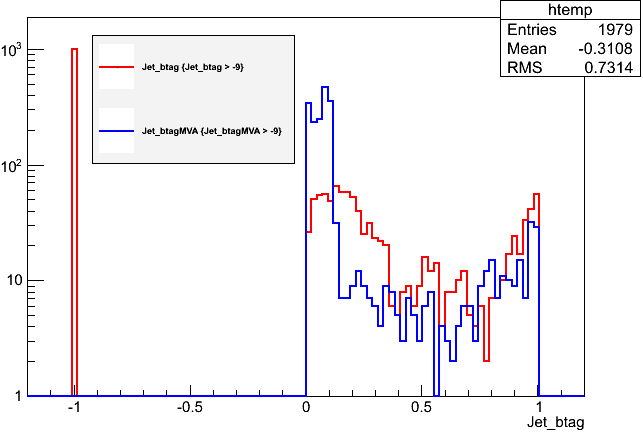

In PatJetAnalyzer.cc we access the information from the Combined Secondary Vertex (CSV) b tagging algorithm and associate discriminator values with the jets. The CSV values are stored in a separate collection in the POET files called a JetTagCollection, which is effectively a vector of associations between jet references and float values (such as a b-tagging discriminator).

#include "DataFormats/BTauReco/interface/JetTag.h"

#include "DataFormats/PatCandidates/interface/Jet.h"

[...]

Handle<std::vector<pat::Jet>> myjets;

iEvent.getByLabel(jetInput, myjets);

[...]

//define b-tag discriminators handle and get the discriminators

for (std::vector<pat::Jet>::const_iterator itjet=myjets->begin(); itjet!=myjets->end(); ++itjet){

[...]

// from the btag collection get the float (second) from the association to this jet.

jet_btag.push_back(itjet->bDiscriminator("combinedSecondaryVertexBJetTags"));

}

You can use the command edmDumpEventContent to investiate other b tagging algorithms available as edm::AssociationVector types. This is an example opening the collections for two alternate taggers--the MVA version of CSV and the high purity track counting tagger, which was the most common tagger in 2011:

// inside the jet loop

jet_btagheb.push_back(itjet->bDiscriminator("simpleSecondaryVertexHighEffBJetTags"));

jet_btagtc.push_back(itjet->bDiscriminator("trackCountingHighEffBJetTags"));

The distributions in ttbar events (excluding events with values of -9 where the tagger was not evaluated) are shown below. The track counting discriminant is quite different and ranges 0-30 or so.

Work in progress

Working Points¶

A jet is considered "b tagged" if the discriminator value exceeds some threshold. Different thresholds will have different efficiencies for identifying true b quark jets and for mis-tagging light quark jets. As we saw for muons and other objects, a "loose" working point will allow the highest mis-tagging rate, while a "tight" working point will sacrifice some correct-tag efficiency to reduce mis-tagging. The CSV algorithm has working points defined based on mis-tagging rate:

- Loose = ~10% mis-tagging = discriminator > 0.244

- Medium = ~1% mis-tagging = discriminator > 0.679

- Tight = ~0.1% mis-tagging = discriminator > 0.898

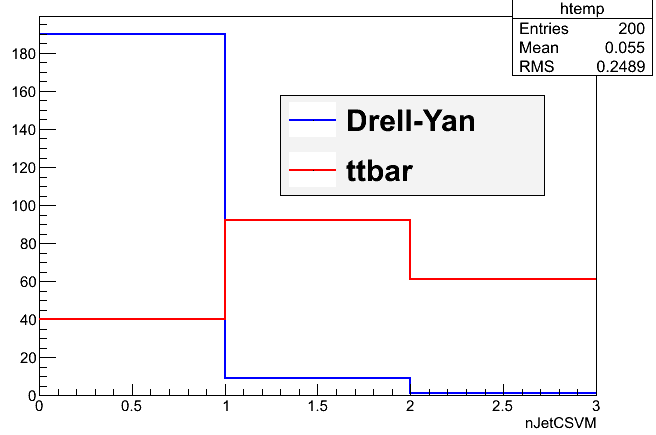

We can count the number of "Medium CSV" b-tagged jets by summing up the number of jets with discriminant values greater than 0.679. After adding a variable declaration and branch we can sum up the counter:

value_jet_nCSVM = 0;

for (std::vector<pat::Jet>::const_iterator itjet=myjets->begin(); itjet!=myjets->end(); ++itjet){

// skipping bits

jet_btag.push_back(itjet->bDiscriminator("combinedSecondaryVertexBJetTags"));

if (jet_btag.at(value_jet_n) > 0.679) value_jet_nCSVM++;

}

We show distributions of the number CSV b jets at the medium working point in Drell-Yan events and top pair events. As expected there are significantly more b jets in the top pair sample.

Work in progress

Data and Simulation Differences¶

When training a tagging algorithm, it is highly probable that the efficiencies for tagging different quark flavors as b jets will vary between simulation and data. These differences must be measured and corrected for using "scale factors" constructed from ratios of the efficiencies from different sources.

The figures below show examples of the b and light quark efficiencies and scale factors as a function of jet momentum read more. Corrections must be applied to make the b-tagging performance match between data and simulation. Read more about these corrections and their uncertainties on this page.

When training a tagging algorithm, it is highly probable that the efficiencies for tagging different quark flavors as b jets will vary between simulation and data. These differences must be measured and corrected for using "scale factors" constructed from ratios of the efficiencies from different sources. The figures below show examples of the b and light quark efficiencies and scale factors as a function of jet momentum read more.

To do

"The figures below" for both paragraphs are missing. Decide whether this part is valid for Run 2 as well.

Work in progress